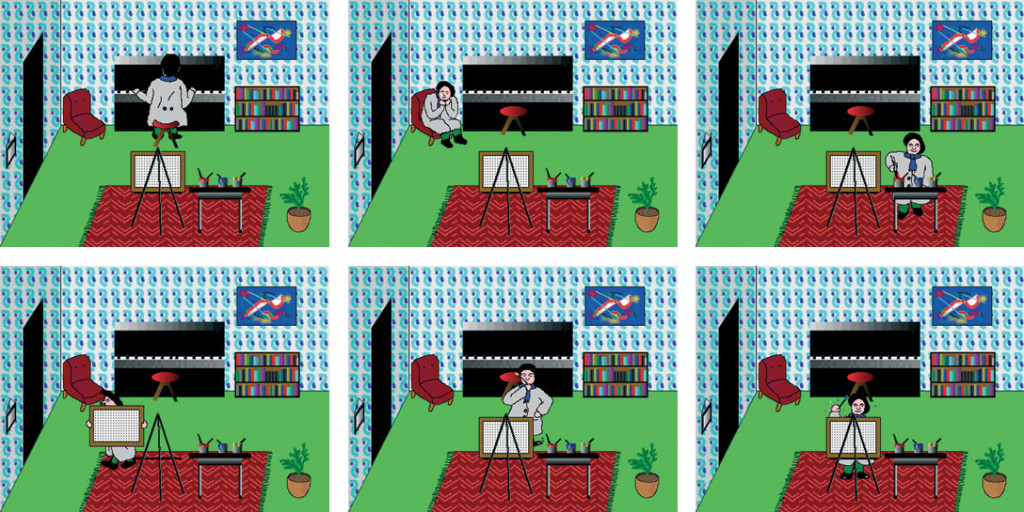

F. Y. Morin – “A day in the life of Raoul Pictor” [cat.], 1994

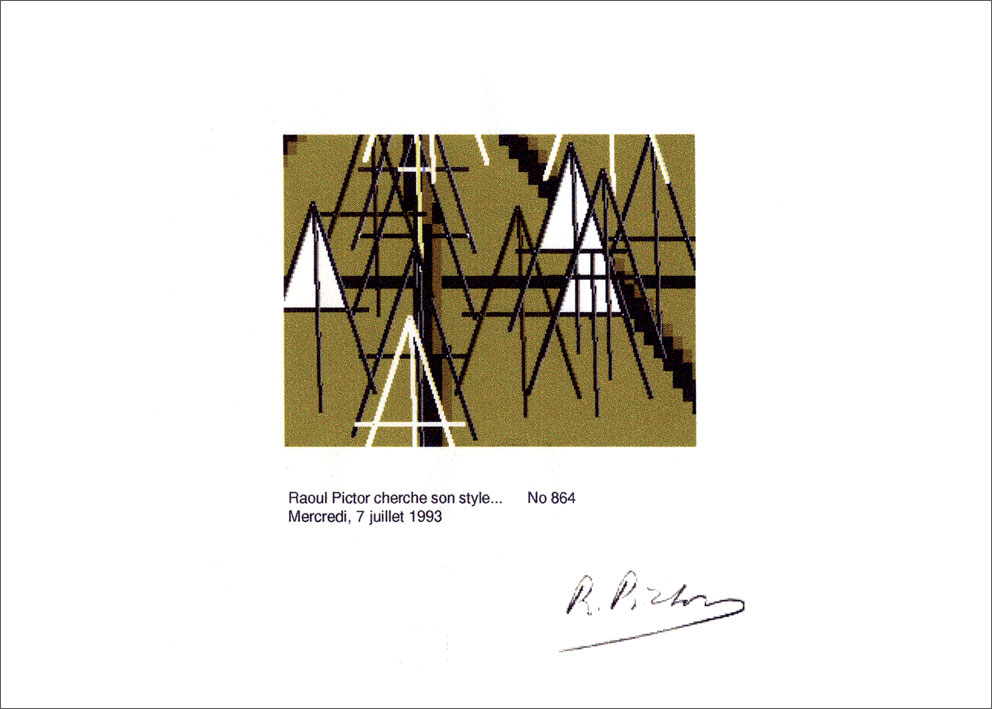

Raoul Pictor cherche son style… (v.1), 1993 – dispositif informatique, ordinateur, imprimante, logiciel / computer device, printer, software – dimensions variables

Awakened by the activation of an internal clock, Raoul appears to us piece by piece, like a ghost, in the room which he uses as his studio. For a few moments, not yet sure of his personal identity, he loses himself in his surroundings, becomes entangled in the bright green trapezium of the fitted carpet or partly snatched up in the drawing of a bookcase, simplified by vertical bars of colour.

As soon as he finds himself, Raoul fervently undertakes his main activity: walking. This exercise is not a goal in itself, it indicates the perplexity of the artist. Decked out in a grey smock, beret fixed onto his head, his hands linked behind his back, Raoul tries out the space in his studio with a touching clumsiness. But when he changes direction he seems to face certain difficulties… is he not confronted with a spatial aporia: how to adjust himself to the illusionary depth of a plane? Raoul’s pacing, a metaphor for the problem of depth, that forever confronts painting, no longer has the virtue of proving motion by doing it, but asserts the possibility of representation. Raoul is a painter – Pictor – primarily by his pacing, obligatory preamble to his art.

To put aside his solemn absorptions the painter is accustomed to playing the piano. During his breaks he also abandons himself in a crudely comfortable armchair nestled into a corner of the room, privileged position for whoever pretends to scrutinize the orthogonality of the phenomenal world. After which, Raoul paints quickly, with an uneasy fervour, in his urgency to fix the outcome of his meditations, longly chewed over during all his comings and goings, before it escapes him. Being a studio-artist his model is mental. No image, picturesque vignette or sublime vision, comes to trouble his clear awareness of relationships. The canvas is finished with large brush-strokes and many gestures, whereupon the artist takes it under his arm and leaves the room by a narrow dark opening; this opening, if we are to grant credit to the Renaissance codes of perspective, symbolises a rectangular opening in the shape of a door.

To note: we know nothing of the work that has just been completed as it was placed on an easel with its back to us, taking the centre position in the studio, and the artist, after having finished his work, took it away without turning it. For the moment Raoul, who has reverted to his primordial electrical state, is linked so intimately to his creation that we can no longer distinguish one from the other, Raoul deprived of a surface, Raoul the algorithm moving in the network of cables, straddling the interface that connects the printer and the computer. From his unrepresented activity, an image is born: a pattern of coloured inks obtained by combining in a landscape format a random selection of elements stored in the programme’s memory. Signed, dated and numbered the work then represents merely one of the terms of the set of probabilities to which Raoul’s creative fervour finally boils down. From here several pressing questions are to be posed:

Does the expression Raoul Pictor seeks his style signify that it will have been found once the music of chance has died, when he has exhausted all possible combinations – without doubt many billions – within the limited framework of his memory? In this hypothesis, if Raoul continues to produce, there will be nothing left for him except to plagiarise himself. Is one to see here a form of rambling or rather consider this as a wonderful lesson in the mysterious mechanics that make artists act? Is not the work of art, whatever its form, whatever materials are employed to embody the form, fundamentally lacking in originality? To the appreciation of the enthusiastic public, which applauds a radical novelty, failing to recognize, beneath the glaring deception of its topicality, a deft or inspired reorganisation of sameness, Raoul offers a less idealistic conception of creation. If after x years of hard labour, he begins to paint canvases that have already come out of his studio, can one fairly reproach him for it, knowing that within his achieved memory his completed work exists, at least potentially, even before he has prepared his palette? A painting that comes out of a printer is therefore always a copy. What privileged status then does the first copy hold? Is it possible to give an ontological legitimacy prohibiting a second or third copy, and finally to them all being reproduced? To the question that opens this passage, we echo the following one, with no pretention of closing the subject: Is it then that, unlike many, who one day believed they had found, Raoul, scrutinizing the boundless but finite corpus of what he has to express, continues to seek?

F. Y. MORIN

(Trad. V. Sordat, D. White)