Raoul Pictor 2023 Featured

To mark the 30th anniversary of “Raoul Pictor seeks his style…” (1993), the Crypto Painter web app is launched, unveiling Raoul Pictor’s new style: “Country Spirit I” on fxhash

To mark the 30th anniversary of “Raoul Pictor seeks his style…” (1993), the Crypto Painter web app is launched, unveiling Raoul Pictor’s new style: “Country Spirit I” on fxhash

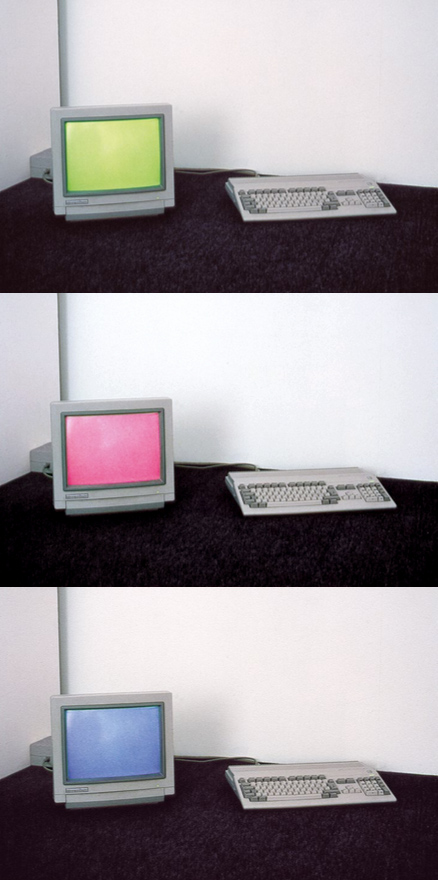

Couleur minute, 1990

computer, monitor, software / ordinateur, écran, logiciel

A monochrome color is displayed on the computer screen and changes each minute.

Couleur Minute online version (revisited version)

Thanks to Matthieu Cherubini for the adaptation.

The link open a new page, use fullscreen mode for the best presentation.

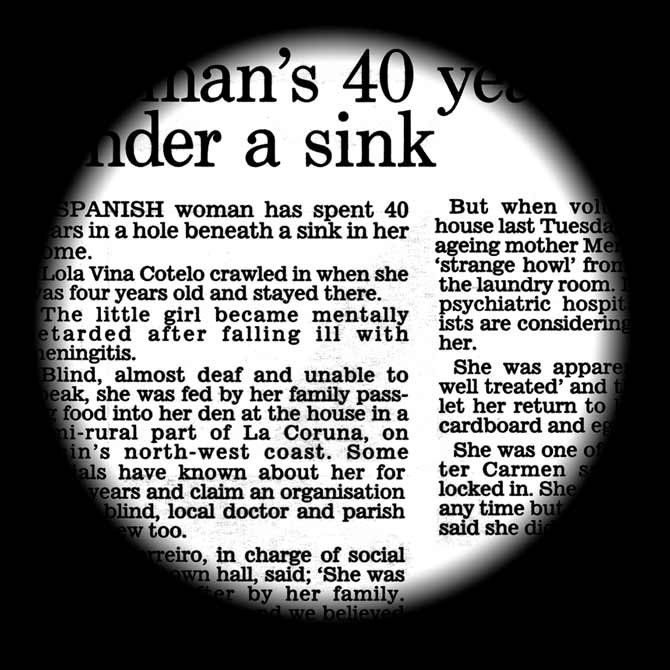

The series “Sur Seurat”, 1994, was made using an HP Deskwriter 500C.

Various images of paintings of Georges Seurat (1859 – 1891) were scanned, reduced in a small version and printed in the worst quality.

HP Deskwriter 500C – 1991 – The first Deskwriter to offer color printing as an option, using interchangeable black and tri-color (CYM) pigment-based inkjet print cartridges.

This system offered the same print quality and speed as the original Deskwriter. Priced at $1,095.

Source:

Twenty Years of Innovation: HP Deskjet Printers 1988 – 2008

Georges Seurat (1859–1891),

Model in Profile (study for Poseuses) (1887),

oil on wood, 24 x 14.6 cm,

Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Georges Seurat (1859–1891),

Alfalfa fields (1885-86),

oil on canvas, 65 x 81.3 cm,

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK.

Georges Seurat (1859–1891),

Model from the Back (study for Poseuses) (1887),

oil on wood, 24.4 x 15.7 cm,

Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Georges Seurat (1859–1891),

Model Standing (study for Poseuses) (1887),

oil on wood, 26 x 17.2 cm,

Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Wikimedia Commons.

Profils perdus, 1994

ordinateur, générateur de petites annonces aléatoires

computer, random generator of classified ads

Profils Perdus (version originale Fr.)

(Hommes & Femmes, 18-40 ans)

Français / French

Profils Perdus (english version)

(Men & Women, 18-40 years old)

Anglais / English

Profils Perdus (Hommes seulement)

(Hommes, 18-40 ans / Men, 18-40 years old)

Français / French only

Profils Perdus (Femmes seulement)

(Femmes, 18-40 ans / Women, 18-40 years old)

Français / French only

Un grand merci à Matthieu Cherubini (mchrbn.net) pour avoir actualisé ce travail en Html 5. Ce générateur a été réalisé à l’origine avec MacroMedia Director.

Pour répondre à certaines demandes, des variantes ont été ajoutées: Hommes ou femmes uniquement, jeunes et moins jeunes…

Vous pouvez utiliser ce travail comme écran de veille avec la fonction plein écran de votre navigateur, ainsi vous vous sentirez moins seul.

Les annonces changent automatiquement toutes les 10 secondes, vous pouvez également cliquer sur l’annonce pour la changer manuellement.

Many thanks to Matthieu Cherubini (mchrbn.net) for making this work available in Html 5. This generator was originally realized with Macromedia Director.

Some people made requests for having customized versions: Men or Women only, young or mature people…

You can use this work like a screen saver with the fullscreen function of your browser, you will then feel less alone.

The classified ads refreshes automatically every 10 seconds , you can also click on the ad to change it manually.

This shockwave work is emulated by Cloud Browser (thank you). With some errors with the countdown, sorry.

in Monography

“People speak about computer art as if it were art in plaster or bronze. That doesn’t really interest me. To represent a computer screen, I prefer to use a bit of fabric mounted on a frame and stick some coloured thumbtacks into it.”

In response to Hervé Graumann’s comment, one might say that we do not necessarily expect a computer artist to depict his computer any more than we would expect a painter to think primarily of painting a picture of paintbrush and pigment. But by the time Pop Art took the floor, there was no denying that a brushstroke could be translated into dots and that the act of painting could be captured in the alien medium of the halftone grid. It was through this form of alienation that Roy Lichtenstein compelled us to reflect not only on the means of expression but also on his subject matter. He represented painting using non-painterly means. And Hervé Graumann achieved his breakthrough on-screen with the antiquated figure of a painter, demonstrating how the “old craft” of painting works using an easel and three pots of paint. Actually, Hervé Graumann’s tools are neither paintbrush and paint nor a computer nor any other means of expression traditionally taught at an art academy. Instead he uses disjunctive changes in vantage point and perspective as well as humour and irony in order to explore questions of reality and art philosophical concerns. Early in life he became acutely aware of being a Francophile with a German name, a name that understandably inspired his penchant for colour [German grau = grey].

For machines, 1996-97 – dispositif informatique, appareils électriques, bande vidéo

computer device, electrical objects, video tape – dimensions variables

“Nonchalance” was the title of an exhibition organised in 1997 by the Centre PasquArt in Biel and subsequently shown at the Academy of the Arts in Berlin. Art of life, autopoiesis, self-reflexion, self-subversion, change of paradigm, crossover, aberration, flaneur are some of the keywords discussed in the accompanying catalogue. Hervé Graumann was represented along other artists such as Pipilotti Rist, Daniele Buetti, Fabrice Gygi, Sylvie Fleury, Thomas Hirschhorn and Christian Marclay. Christian Robert-Tissot’s contribution on the CD of the award-winning catalogue publication was called Assez nul (Pretty Shitty), L/B’s Reduzierte Schwerkraft (Gravity Reduced), Stefan Altenburger’s Unsaved Memories and Hervé Graumann’s Music for Printer. To me Hervé Graumann was the quintessential exponent of “Nonchalance”. His installation For machines confronted us with electric household appliances, a hairdryer, a drill, a radio, a record player, lamps, etc., which were programmed to run alternately and simultaneously. The installation included a video of everyday scenes that Hervé Graumann had filmed with his seven-year-old daughter. We one-dimensionally functioning, ambitious everyday people can only dream of the insouciance conveyed by this art and its exquisitely light touch with reality. I know that the dictionary lists a number of negative meanings for “nonchalance” such as carelessness, disdain or disinterest. But we had discovered a word that had lost its function as a deterrent; we saw it as an expanded term for creative dream dancers and jugglers.

Without entirely dismissing the quality of nonchalance in Hervé Graumann’s work, I do, in retrospect, take a more differentiated view of his artistic developments. I’ve been keeping track of his work for over 10 years and was more than enthusiastic about Raoul Pictor’s first appearance, about hard on soft and Blanc sur Blanc. It is quite natural that the ongoing, developing art of Raoul Pictor initially formed the core of his oeuvre, for it is situated as much in virtual cyberspace and as it is in the space of the museum. And it is equally natural that Graumann continues to dream of an automatic assistant who can generate a host of original pictures here and there and everywhere in the world where he is invited, thereby undermining the concept of the original and making a droll dig at the art trade. Hervé Graumann has often drawn my attention to the beauty of some of the resulting pictures. I do not dispute their aesthetic, but Raoul Pictor obviously also challenges the principle of individual creative activity. He is useful as a metaphor for the shift of interest away from a physically unique picture to visually generated reflection upon artistic processes. Hervé Graumann, the Neodadaist is an astute thinker, who ceaselesly calls into question the idea of the autonomous picture, of its generation and its presentation.

This publication is the first to trace the playful and yet rigorously logical path that has led to a coherent oeuvre in which there is much to discover and to admire, especially in the beginnings which emerged alongside the rise of digital technology. Hervé Graumann’s multi-dimensional approach is underrated. No matter what he does, his stringent objectives preclude all banality; he has been known to be extremely severe in his assessment of colleagues who produce nonchalant art and succumb to the temptation of the playful randomness posed by the world of digitally generated images. For more than 10 years he has been exploring the role of the picture as a mimetic phenomenon. What is a canvas? What is a picture frame? What is acrylic paint? What is paint on the computer screen and what happens when a plotter prints pixels and delivers arbitrary identical images? How do we react when we see enlarged pixels painted on a canvas, knowing full well that the paintbrush is perfectly capable of handling organic transitions? What is a printed handwritten signature? What is a machine-made date, listing day, hour and minute, and what does the unique automatic dedication, triggered by the addressee and send to him/herself, mean? It’s exactly like asking an unknown writer for an autograph after a reading, to which he complies with a smile upon asking how the name is spelled.

We will enjoy Graumann’s work only if we also enjoy inquiring into artistic strategies and are willing to surrender a few beloved rules and artistic attitudes concerning individual style and the conventional properties of originality in pictures. We must not fall in love with the randomly generated colour combinations of Raoul Pictor’s pictorial creations even if Hervé Graumann is pleased to find these products framed and mounted on the wall of a room, to wit: computer prints sold for 10 francs or, on another occasion, a free handout for viewers. The comic-like animated image of Raoul Pictor is the final performance of a romantic artist or rather the acronymic caricature of the stereotype of creativity. I sometimes long for that stereotype when I visit a studio filled with computers and bare walls, and am offered a glass of orange juice. Raoul Pictor is the radical destruction of a cherished artist myth that can only function as animated film in today’s age of genetic technology.

Ever since we began making copies of animals, plants and human beings, the need for mimetic creation has lost its attractiveness. Why should we copy reality? Cloning is the ultimate unsurpassable act of artistic creation. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image or any likeness of any thing – and that includes copying nature! Nature doesn’t want to be copied, having demonstrated for thousands of years that it — and we as part of it — generate natural multiplicity instead of reproducing, says the teacher of ethics to the genetic scientist. By cloning, we want to overrule the principles of time and transience. The thought of eternity never fails to seduce the egomania of the human animal. But it cancels out the life principle of constant change and re-creation and the principle of becoming and passing away. Concerned about unpredictable dangers, we try to restrict our potential faculties, just as healthy commonsense has led us to reduce the potential of nuclear arms technology for fear of total annihilation. To compensate, we indulge in virtual expansion. Reality has exploded, expanding into boundless spaces.

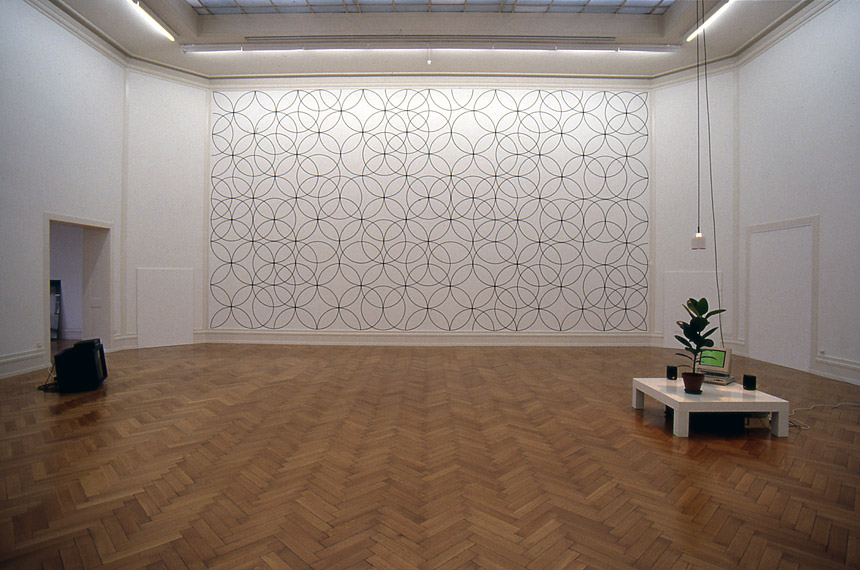

Pattern – Vanité 2b, 2003 – installation, objets divers / installation, sundry objects – 400 x 500 cm.

When Hervé Graumann makes gridlike copies of reality and presents them to us in three dimensions – which we can generate onscreen using the right program and pressing the right key – he is mentally anticipating a reality that a keystroke can reproduce. It may well be that no one has yet realized just how revolutionary Hervé Graumann’s thoughts are. We involve ourselves in ethical, legalistic discussions about cloning living creatures; Graumann translates virtual expansion back into reality. A serious matter served up with disarming nonchalance. The CD-rom as a menu, smarties or ecstasy pills, syringes, cookies, doses of medication for morning, noon and evening, hallucinogens, sedatives and stimulants in the form of sushi: a metaphoric guessing game, a play of illusions, an appeal to differentiated perception and thinking, prodding us to analyse manipulated reality and think about the perception of complex processes. Nonchalant, yes. But the dream dancer, doing multidimensional pirouettes on the stage of our retinas, wants to shake us out of the anesthetic coma of pictorial consumption. Graumann’s enigmatic visual dreams have the mischievous quality of a wakeup call.

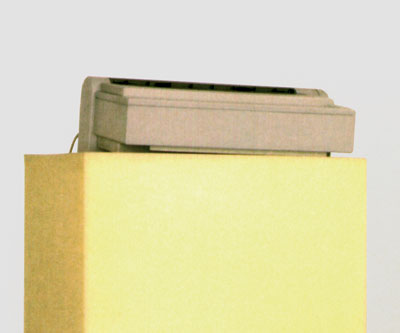

And here we are, back at the beginning of the 20th century with the Dadaists, who expanded expression in all directions and blithely subverted cherished conventions and traditions, or with the ready-mades that took the magic out of established principles of art and still manage to bewilder contemporaries today. Ancestral portraits are legion but Graumann does not want to be linked with the super fathers of the early 20th century. In time, however, he will inevitably be associated and reliably compared with more recent contemporaries like Giulio Paolini, Martin Kippenberger or Markus Raetz. We shall leave it at that for the moment because Hervé Graumann steadfastly exploits the new visual technologies and is, undoubtedly, a pioneer in the exploration of these new visual worlds. Nonetheless, although he is a child of the computer age, he does not ignore paintbrush and paint, and he plays with the quality of the new materials until he has created new forms of watercolors. When he places a chirping printer, from a generation which has since vanished into obsolescence, on a foam rubber stand, the supposed stability of primary reality becomes extremely precarious. That is more than a visualized play on the words ‘hard’ and ‘soft’. It is also an attempt to extract a maximum of poetry from the short-lived realities of modern-day life. It is tempting to speak of a romantic dreamer again, of one who manages to find the most enchanting cubbyholes and chambers in Plato’s cave system despite the flagrant economic underpinnings that drive this technology.

For me, the computer is a luxurious, comfortably glorified typewriter and I have absolutely no notion of programming. That makes me wonder whether I have a fundamentally different perception of this artist’s oeuvre than someone who possesses skills similar to Hervé Graumann’s own and can therefore easily follow and understand how his ideas are generated. Whatever the case, the appeal of Graumann’s work is obviously as accessible to me as it is to a younger generation of viewers and computer adepts. The work vaguely hints at the dimensions of future virtual art spaces but it is also inseparably linked up with art history and the old aesthetic concepts of earlier periods.

Graumann raises a difficult question during the interview when he asks whether we human beings should be controlling computers, or vice versa. He immediately comes up with examples, anticipating those who tend to reject the dominance of the machine and consider the idea absurd. Graumann keeps abreast of technical developments, always playfully entwining and encircling them with reflections and questions. He takes them in with childlike wonder, turns them upside down, peers under surfaces and into the machines themselves, listens to their sounds and adjusts to their growing speed and ever new potential, like someone who does not have to work with them but is simply allowed to play with them. The computer is a discovery machine and he can use it and its latest programmes in the sense intended by those who invented them, but he can also gaze at the computer from a great distance as if it were a ladder to the skies.

Humour in art is always a sign of uninhibited experimentation and reflection. Irony appears to be Graumann’s constant companion. It gives him the necessary detachment. But irony not only requires the nonchalance of free association and improvisation; it also demands a discerning mind and self-discipline. As viewers we tend to look only at the finished works. Eliminating and systematically avoiding irrelevant temptations in order to follow a goal that is as yet unknown – that is the uncharted territory into which pioneers venture to carve paths of their own.

Andreas Meier

Translation: Catherine Schelbert

link: Hard on soft post

in Monography

« On parle d’art numérique comme on pourrait parler d’art en plâtre ou d’art en bronze. Cela ne m’intéresse pas vraiment. Pour représenter un écran d’ordinateur, je préfère utiliser une petite toile montée sur châssis et y planter des punaises colorées. »

Pixels, 1991 – punaises colorées sur toile / coloured thumbtacks on canvas – 24 x 33 cm.

À ces propos d’Hervé Graumann, nous pourrions objecter que nous n’attendons pas forcément de la part d’un artiste plasticien créateur d’œuvres numériques qu’il représente son ordinateur, tout comme nous n’attendons pas qu’un peintre songe d’abord à peindre le pinceau et la peinture. Mais depuis le pop art, il est généralement admis qu’il est possible de traduire un trait de pinceau en points de trame et que l’on peut donc fixer l’acte de peindre par un autre média, celui de la trame d’impression (également peinte). Grâce à cette composante de distanciation, Roy Lichtenstein pouvait communiquer une réflexion non seulement sur le moyen d’expression mais aussi sur l’objet qu’il représentait. Il a ainsi représenté la peinture avec des moyens non picturaux. Et Hervé Graumann a obtenu son premier grand succès grâce à la figure désuète d’un peintre qui fit la démonstration, sur l’écran du moniteur, de ce « vieux métier » de l’artiste peintre travaillant avec un chevalet et trois pots de peinture. Enfin, le vrai outillage d’Hervé Graumann n’est ni le pinceau ni la peinture ni un ordinateur ou quelque moyen d’expression enseigné traditionnellement aux beaux-arts. Son travail repose surtout sur la brusque alternance de regards et de perspectives, ou encore sur des moyens d’expression teintés d’humour et d’ironie, qui lui servent à aborder tant la réalité que des questions concernant la philosophie de l’art. Graumann, qui porte un nom allemand tout en étant francophone, a très tôt pris conscience du phénomène de son patronyme [trad. littérale : homme gris], et nous n’avons aucun mal à comprendre que celui-ci l’invite à la couleur.

For machines, 1996-97 – dispositif informatique, appareils électriques, bande vidéo

computer device, electrical objects, video tape – dimensions variables

« Nonchalance » était le titre d’une exposition organisée en 1997 au Centre PasquArt à Bienne, qui a été ensuite montrée à l’Académie des Arts de Berlin. Art de vie, autopoïèse, autoréflexion, autosubversion, changement de paradigmes, crossover, déviance, flâneur, tels étaient certains parmi les mots-clefs évoqués dans le catalogue. Hervé Graumann était présenté aux côtés de Pipilotti Rist, Daniele Buetti, Fabrice Gygi, Sylvie Fleury, Thomas Hirschhorn, Christian Marclay et d’autres artistes. La contribution de Christian Robert-Tissot pour le CD du catalogue couronné par un prix s’intitulait « Assez nul », celle de L/B « Gravité réduite », celle de Stefan Altenburger « Unsaved Memories » et celle d’Hervé Graumann « Music for Printer ». Hervé Graumann était pour moi le représentant typique de la nonchalance en art. Son installation For machines nous confrontait à des ustensiles électriques, tels qu’un sèche-cheveux, une perceuse, un poste de radio, un tourne-disque, des lampes, etc., qui étaient, alternativement et ensemble, mis en et hors fonction par le logiciel. Parallèlement, sur un moniteur, un film vidéo était diffusé montrant des scènes de la vie courante tournées par l’artiste en compagnie de sa fille de sept ans. De l’insouciance transmise par cet art, c’est-à-dire de cet effleurement de la réalité, nous en rêvons, nous les hommes du quotidien qui fonctionnons de manière unidimensionnelle. Je sais que le dictionnaire propose des définitions plutôt péjoratives du mot « nonchalance », telles quemanque de soin, négligence, ou encore manque d’ardeur. Mais là, nous avions découvert un mot qui avait perdu son effet néfaste. Pour nous, il recouvrait une notion plus large, celle désignant des rêveurs et des saltimbanques inventifs.

Sans vouloir pour autant contester cette qualité de nonchalance propre à Hervé Graumann, je le considère aujourd’hui, au regard de toute son évolution de plasticien créateur, de manière plus nuancée. J’observe son travail depuis plus de dix ans, et je n’ai pas seulement été enthousiaste de la première apparition de son personnage Raoul Pictor, de Hard on Soft ou de Blanc sur Blanc. La nature de son œuvre même, qui s’exprime dans le cyberspace et aussi dans l’espace muséal, peut expliquerque le travail autour de Raoul Pictor, en perpétuelle gestation, ait eu une position centrale. Bien sûr, il rêve toujours de son assistant automatique qui génère ici et là, puis partout dans le monde où il est invité, des quantités d’images originales, jouant ainsi un tour à la sacro-sainte notion d’œuvre d’art originale et, par conséquent, au business de l’art. À plusieurs reprises, Hervé Graumann a attiré mon attention sur la beauté de certaines de ces images. Je ne l’ai pas contesté, mais Raoul Pictor est effectivement une provocation à l’encontre du principe de l’activité créatrice individuelle. Il est apte à servir de métaphore au changement progressif de nos valeurs qui se déplacent de l’admiration pour une image matériellement unique vers une réflexion sur les processus créateurs générée par la sensation visuelle. Hervé Graumann, le néo-dadaïste, est un penseur perspicace qui pose sans cesse la question de l’idée de l’image autonome, de sa genèse et de sa présentation.

Cet ouvrage retrace pour la première fois le parcours menant à un ensemble d’œuvres cohérent, aussi ludique que logique, parmi lequel il s’agit, rétrospectivement, de découvrir et d’apprécier beaucoup d’aspects, surtout au début de sa carrière qui se développe parallèlement à la technologie numérique. On sous-estime le caractère multidimensionnel du travail d’Hervé Graumann. Là où il évolue, il exclut, avec détermination, toute banalité, et il porte parfois un jugement très sévère sur certains collègues qui réalisent un art nonchalant et se laissent tenter, dans l’univers de la création d’images numériques, par ce qui se prêteà un jeu de production arbitraire.Il s’emploie depuis plus de dix ans à sonder le principe de l’usage mimétique des images. Qu’est-ce qu’une toile ? Qu’est-ce qu’un cadre ? Qu’est-ce que la peinture acrylique ? Qu’est-ce que la couleur sur un écran, et qu’est-ce qui se passe quand un plotter imprime les pixels et fournit des images identiques à volonté ? Comment réagissons-nous quand nous voyons des pixels peints, agrandis, sur une toile, d’autant plus que nous attendons d’un pinceau, à juste titre, qu’il soit capable de créer des transitions organiques ? Qu’est-ce qu’une signature manuscrite imprimée ? Qu’est-ce que la datation produite par une machine, avec l’indication du jour, de l’heure et de la minute, et que signifie une dédicace unique, automatique, déclenchée par le destinataire et adressée à lui-même ? C’est exactement comme si on sollicitait un auteur inconnu, lors d’une lecture, de dédicacer un de ses livres, dédicace que l’auteur accorde en souriant, après avoir demandé l’orthographe du nom.

Ne peut développer une passion pour le travail d’Hervé Graumann que celui qui aurait envie d’interpeller les fondements des stratégies artistiques et d’écarter quelques-uns des principes et attitudes propres à l’art auxquels on s’était attachés jusque-là, qui ont trait au style individuel et aux caractéristiques traditionnels de l’œuvre d’art originale. Bien sûr, il serait malvenu de succomber aux créations de Raoul Pictor, compositions de couleurs produites par le hasard, même si Hervé Graumann se réjouit de voir ces images encadrées et accrochées sur les murs d’un salon. Des tirages d’ordinateur qui sont, selon les cas, vendus dix francs suisses ou offerts gratuitement. Raoul Pictor, ce personnage au graphisme de bande dessinée, est la dernière entrée en scène d’un artiste romantique, la caricature abrégée d’un stéréotype de créateur. C’est ce créateur après lequel je languis parfois quand je me retrouve, lors de visites d’ateliers, face à des ordinateurs et des murs nus, et que l’on me sert un jus d’orange. Raoul Pictor est la destruction radicale d’un mythe de l’artiste auquel on s’était attaché, qui, à l’ère de la génétique, ne fonctionne plus que sur le mode d’un film d’animation.

Depuis que nous avons commencé à copier des animaux, des plantes et des hommes, le besoin créateur mimétique a perdu de son attrait. Pourquoi copierons-nous la réalité ? Le clonage est le processus créateur ultime que l’on ne saurait surpasser. Tu ne feras pas d’idole, aucune image de ce qui est sur la terre, voilà l’avertissement que nous proférons en nous autorisant de la Bible ! La nature s’y refuse après nous avoir démontré concrètement, pendant des siècles, qu’elle – et nous en elle – engendrons la diversité naturelle au lieu de reproduire, dit le philosophe de l’éthique au généticien. Avec le clonage, nous cherchons à abroger le principe du temps et de l’éphémère. L’idée d’éternité est très séduisante pour l’animal humain avec ses prétentions d’ego. Mais ce qui est annulé c’est pourtant le principe vital, continuel, de la transformation et de la création nouvelle ainsi que le principe du devenir et de la disparition. Non sans quelques réserves quant aux dangers incalculables, nous essayons de limiter notre pouvoir potentiel, de même que le bon sens nous a amené, en raison de la peur d’une destruction totale, à réduire les possibilités de la technologie de l’arme nucléaire. Nous avons compensé la renonciation avec les possibilités d’une expansion virtuelle. Telle une explosion, la réalité s’est répandue dans des espaces d’une immensité inconcevable.

Pattern – Vanité 2b, 2003 – installation, objets divers / installation, sundry objects – 400 x 500 cm.

Quand Hervé Graumann copie la réalité au moyen de grilles et nous en fait une démonstration tridimensionnelle, c’est alors l’anticipation mentale d’une réalité que l’on peut produire sur l’écran et multiplier au moyen des touches du clavier avec les programmes et les fonctions appropriés. Peut-être n’a-t-on pas encore réellement compris l’importance capitale, si actuelle, de sa réflexion. Nous nous empêtrons dans des discussions éthiques et juridiques sur le clonage d’êtres vivants, Graumann retraduit l’expansion virtuelle pour la ramener dans la réalité. Une affaire sérieuse présentée nonchalamment. Le CD-ROM au menu, des Smarties ou des comprimés d’extasy, des seringues, des cookies, des médicaments préalablement dosés pour matin, midi et soir, des substances hallucinogènes, sédatives et stimulantes, le tout servi sous forme de sushi. C’est un rébus de métaphores et un embrouillamini ludique comme une invitation à une perception et réflexion subtile, un appel à analyser cette réalité manipulée et à y déceler les processus complexes. Nonchalant, certes. Mais le doux rêveur qui danse devant nos yeux des pirouettes multidimensionnelles, nous secoue pour enfin nous sortir de notre sommeil de Belle au bois dormant, si typique de la consommation anesthésique inconsciente. Ses énigmatiques « rêves-images » ont les qualités malicieuses d’un réveil.

Et nous voici encore une fois au début du siècle, en compagnie des dadaïstes, qui ont élargi les rêves expressifs dans toutes les directions et qui ont remis en question les traditions et les habitudes faciles, voici des ready-made qui ont désenchanté les vieux principes de l’art, toujours capables de troubler les contemporains. Ce n’est ni le lieu ni la place pour présenter toute la galerie des ancêtres. Chemin a plus d’importance, aux yeux de Graumann, que Duchemin. Il ne souhaite pas être mis en rapport avec les pères surpuissants du début du XXe siècle. Mais on le mettra forcément, le moment venu, en rapport avec Giulio Paolini, par exemple, ou avec Martin Kippenberger et Markus Raetz. Laissons de côté, pour l’instant, ces allusions ne serait-ce que parce qu’Hervé Graumann évolue avec une parfaite logique au cœur des nouvelles technologies de l’image et qu’il peut revendiquer son statut de pionnier quant à la réflexion visuelle de ces univers picturaux. Enfant de l’ère informatique, il n’oublie pas cependant de manier le pinceau et la peinture, et il joue avec les qualités des nouveaux matériaux jusqu’à ce qu’il arrive à créer de nouvelles formes d’aquarelles. Quand il place sur un socle en mousse une imprimante, au bruit grésillant, d’un ancien modèle qui a depuis disparu du marché, alors la réalité primaire se met à vaciller. C’est bien plus qu’un jeu de mots visualisé avec hard et soft (dur et mou, hardware et software, matériel et logiciel). Il s’agit aussi d’une tentative pour tirer un maximum de poésie de chacune de ces réalités changeantes. On serait de nouveau tenté d’évoquer le rêveur romantique qui révèle à la pure économie, instigatrice constante de cette technologie, les espaces contigus et les recoins les plus magiques au sein de la vaste grotte platonicienne.

La question que je me pose : moi, qui utilise l’ordinateur comme une grosse machine à écrire sophistiquée et pratique, et ne connaissant rien au métier de programmeur, ai-je une perception fondamentalement différente de cette œuvre qu’une personne dont les capacités égalent celles d’Hervé Graumann et qui arrive à suivre les étapes de la naissance de ces idées avec une même légèreté naturelle. Cette question est manifestement sans intérêt, car je considère être la preuve du fait que l’attrait du travail de Graumann est tout aussi accessible à moi qu’à la jeune génération de spectateurs et d’habiles utilisateurs d’informatique. Vaguement, de futurs espaces artistiques virtuels s’esquissent, avec de nouvelles dimensions, mais son travail maintient une relation à l’histoire de l’art et aux notions esthétiques des anciennes époques artistiques.

Une question qu’il a soulevée lors de l’interview réalisé pour cette publication prête à discussion : « Est-ce l’homme qui doit surveiller l’ordinateur ou l’inverse ? » Pour anticiper aussitôt sur ceux qui auraient tendance à rejeter la prédominance de la machine en la faisant passer pour absurde. Graumann est au diapason des évolutions techniques, mais il les orne et les entoure, d’une manière très ludique, de réflexions et de questions. Il les perçoit comme un enfant ébahi, les retourne, les met tête en bas, il scrute ce qui se trouve sous les surfaces et à l’intérieur de la machine, il écoute les bruits, s’adapte aux vitesses et aux nouvelles possibilités, joue avec des termes nouvellement créés, avec le signifiant et avec le signifié. Il apprécie ces instruments comme quelqu’un qui n’est pas obligé de travailler avec eux, mais qui a le droit de jouer avec eux. L’ordinateur est une machine faite pour les découvertes, et il peut utiliser les ordinateurs et leurs plus récents programmes selon les intentions de leurs inventeurs, tout comme il peut regarder l’ordinateur à distance comme s’il était une échelle de Jacob.

L’humour dans l’art est toujours signe d’une faculté d’expérimentation et de réflexion très naturelles. L’ironie semble toujours accompagner Graumann. Elle lui offre la distance nécessaire. Mais l’ironie n’exige pas seulement un mode d’association nonchalant, l’improvisation, mais aussi la lucidité et l’autodiscipline. En tant que spectateur, on est disposé de ne voir que l’œuvre accomplie. Faire un choix précis et éviter systématiquement les tentations superficielles, en ne perdant jamais des yeux l’objectif encore inconnu, c’est là le territoire où les pionniers trouvent leur voie.

A.M.

Traduction de l’allemand Silke Hass

link: Hard on soft post

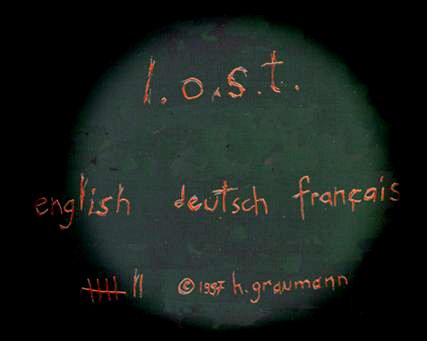

When Hervé Graumann created a painter-machine, gave it a name and something to work with (ink, paper, and electricity), he did not realize that he had just created a personage which was to plunge him into obsession and challenge the very individuality of his artistic production. If at first “Raoul Pictor” was indeed something produced by Graumann (after all, hadn’t he written all the lines of code in the program?), it now seems it has gotten paint all over its author. Is it possible that the author, an individual who creates and expresses himself, has now been reduced to the mute speech of his machines?

Without hiding behind such questions of identity, Graumann nonetheless situates his work on that abstract, blurry boundary between author and machine. In his project for documenta’s website, it is hard to know who is expressing himself and who is the depressive, abandoned figure calling for help. Yet the latter is doing just that from a specific place on the World Wide Web. Furthermore, he can only be reached there. (Or is he in fact only on the viewer’s screen)?

In fact, it all begins with a blank screen. By moving the cursor with a mouse over the screen, one moves a white disc that looks something like the beam of a flashlight. Little by little, this shape reveals a text that is legible only by sweeping it with the beam of light: “ugh! this isn’t my day,” then “no” and “for how long?” Or “total darkness, locked up,” then “alone” and “locked up, alone, lost! alone, forgotten.” One can never predict where the words, brought to life but broken to bits and spread over the screen, written in small letters or big, will appear next; nor can we say whence they come, nor who is uttering them. Yet suddenly a window appears, allowing one to write directly to lost@sgg.ch, like a despairing appeal for contact. It remains to be seen who the person to be contacted will be, or what will become of the messages.

As much as man may be seduced by the machine, he nonetheless fears it. Similarly, Graumann’s work plays on both these feelings. Neither a positivist nor a catastrophist, he can make machines execute a number of operations sufficient to feign their independence, enough for them to have an opportunity to seduce us, thereby revealing yet another form of human genius.

Simon Lamunière

![]() you need the shockwave plugin to see l.o.s.t.

you need the shockwave plugin to see l.o.s.t.

The Hole (d’après l.o.s.t.), 2000 – sérigraphie noir et blanc / black and white serigraphy – 70 x 100 cm.

Hard on soft, 1993 – ordinateur, imprimante à aiguilles, socle en mousse / computer, dot matrix printer, foam base – 145 x 50 x 40 cm.

audio file of one of the 7 compositions

View: Andata Ritorno Gallery, Geneva, 1994

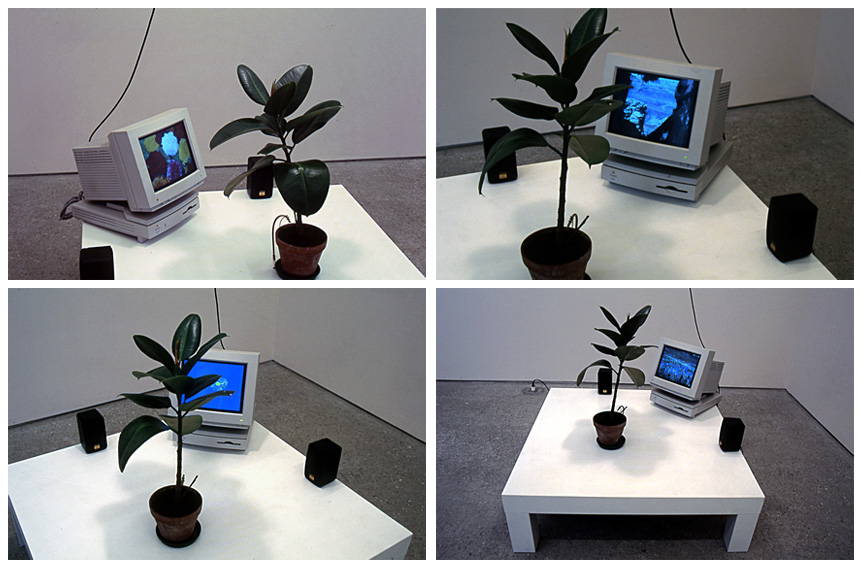

Green plant entertainment, 1994-95 – dispositif informatique, interface, logiciel, son, eau, lumière, plante verte computer device, interface, software, sound, water, light, pot plant – dimensions variables

Exhibition view – “White noise”, Kunsthalle Bern, 1998

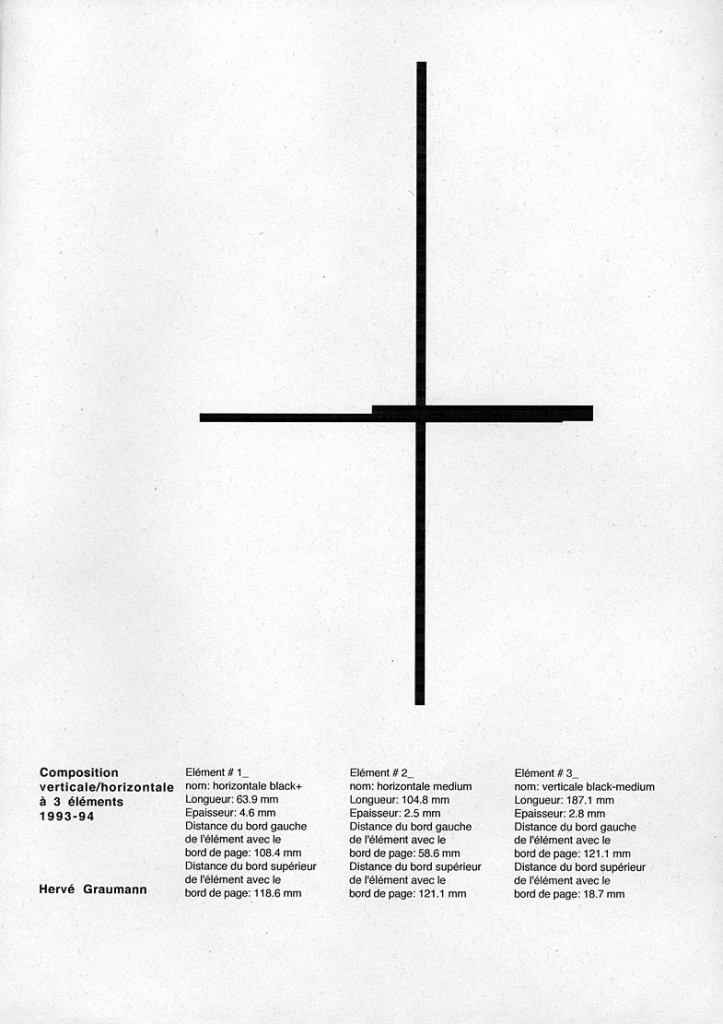

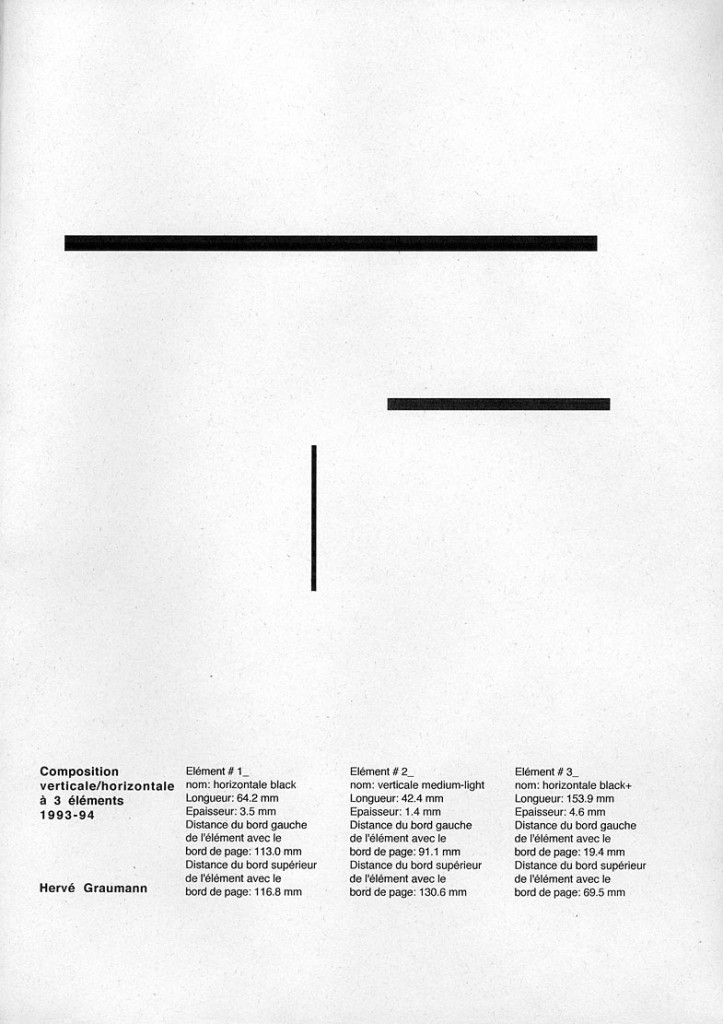

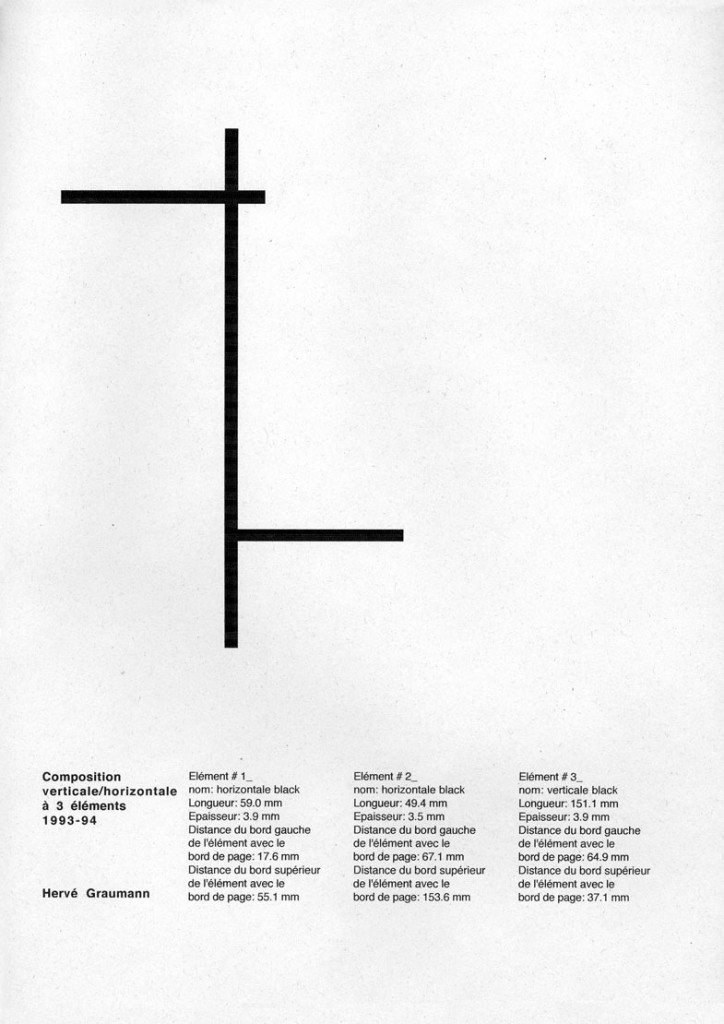

Raoul Pictor cherche son style… (v.1), 1993 – dispositif informatique, ordinateur, imprimante, logiciel / computer device, printer, software – dimensions variables

Awakened by the activation of an internal clock, Raoul appears to us piece by piece, like a ghost, in the room which he uses as his studio. For a few moments, not yet sure of his personal identity, he loses himself in his surroundings, becomes entangled in the bright green trapezium of the fitted carpet or partly snatched up in the drawing of a bookcase, simplified by vertical bars of colour.

As soon as he finds himself, Raoul fervently undertakes his main activity: walking. This exercise is not a goal in itself, it indicates the perplexity of the artist. Decked out in a grey smock, beret fixed onto his head, his hands linked behind his back, Raoul tries out the space in his studio with a touching clumsiness. But when he changes direction he seems to face certain difficulties… is he not confronted with a spatial aporia: how to adjust himself to the illusionary depth of a plane? Raoul’s pacing, a metaphor for the problem of depth, that forever confronts painting, no longer has the virtue of proving motion by doing it, but asserts the possibility of representation. Raoul is a painter – Pictor – primarily by his pacing, obligatory preamble to his art.

To put aside his solemn absorptions the painter is accustomed to playing the piano. During his breaks he also abandons himself in a crudely comfortable armchair nestled into a corner of the room, privileged position for whoever pretends to scrutinize the orthogonality of the phenomenal world. After which, Raoul paints quickly, with an uneasy fervour, in his urgency to fix the outcome of his meditations, longly chewed over during all his comings and goings, before it escapes him. Being a studio-artist his model is mental. No image, picturesque vignette or sublime vision, comes to trouble his clear awareness of relationships. The canvas is finished with large brush-strokes and many gestures, whereupon the artist takes it under his arm and leaves the room by a narrow dark opening; this opening, if we are to grant credit to the Renaissance codes of perspective, symbolises a rectangular opening in the shape of a door.

To note: we know nothing of the work that has just been completed as it was placed on an easel with its back to us, taking the centre position in the studio, and the artist, after having finished his work, took it away without turning it. For the moment Raoul, who has reverted to his primordial electrical state, is linked so intimately to his creation that we can no longer distinguish one from the other, Raoul deprived of a surface, Raoul the algorithm moving in the network of cables, straddling the interface that connects the printer and the computer. From his unrepresented activity, an image is born: a pattern of coloured inks obtained by combining in a landscape format a random selection of elements stored in the programme’s memory. Signed, dated and numbered the work then represents merely one of the terms of the set of probabilities to which Raoul’s creative fervour finally boils down. From here several pressing questions are to be posed:

Does the expression Raoul Pictor seeks his style signify that it will have been found once the music of chance has died, when he has exhausted all possible combinations – without doubt many billions – within the limited framework of his memory? In this hypothesis, if Raoul continues to produce, there will be nothing left for him except to plagiarise himself. Is one to see here a form of rambling or rather consider this as a wonderful lesson in the mysterious mechanics that make artists act? Is not the work of art, whatever its form, whatever materials are employed to embody the form, fundamentally lacking in originality? To the appreciation of the enthusiastic public, which applauds a radical novelty, failing to recognize, beneath the glaring deception of its topicality, a deft or inspired reorganisation of sameness, Raoul offers a less idealistic conception of creation. If after x years of hard labour, he begins to paint canvases that have already come out of his studio, can one fairly reproach him for it, knowing that within his achieved memory his completed work exists, at least potentially, even before he has prepared his palette? A painting that comes out of a printer is therefore always a copy. What privileged status then does the first copy hold? Is it possible to give an ontological legitimacy prohibiting a second or third copy, and finally to them all being reproduced? To the question that opens this passage, we echo the following one, with no pretention of closing the subject: Is it then that, unlike many, who one day believed they had found, Raoul, scrutinizing the boundless but finite corpus of what he has to express, continues to seek?

F. Y. MORIN

(Trad. V. Sordat, D. White)